Understanding std::hardware_destructive_interference_size and std::hardware_constructive_interference_size(理解 std::hardware_corruption_interference_size 和 std::hardware_constructive_interference_size)

问题描述

C++17 添加了 std::hardware_corruption_interference_size 和 <代码>std::hardware_constructive_interference_size.首先,我认为这只是一种获取 L1 缓存行大小的可移植方式,但这过于简单化了.

问题:

- 这些常量与 L1 缓存行大小有什么关系?

- 是否有一个很好的例子来展示他们的用例?

- 两者都定义了

static constexpr.如果您构建一个二进制文件并在具有不同缓存行大小的其他机器上执行它,这不是问题吗?当您不确定代码将在哪台机器上运行时,它如何防止这种情况下的错误共享?

这些常量的目的确实是为了获得缓存行的大小.阅读它们的基本原理的最佳位置是提案本身:

http://www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg21/docs/papers/2016/p0154r1.html

为了便于阅读,我将在此处引用部分理由:

<块引用>[...] 不干扰(一阶)的内存粒度[是] 通常称为缓存行大小.

缓存行大小的使用分为两大类:

- 避免具有来自不同线程的时间上不相交的运行时访问模式的对象之间的破坏性干扰(错误共享).

- 促进具有临时本地运行时访问模式的对象之间的建设性干扰(真正共享).

这个有用的实现数量最重要的问题是当前实践中用于确定其价值的方法的可移植性有问题,尽管它们作为一个群体普遍存在和流行.[...]

我们的目标是为此贡献一个适度的发明,这个数量的抽象可以通过实现为给定目的保守地定义:

- 破坏性干扰大小:适合作为两个对象之间的偏移量的数字,以避免由于来自不同线程的不同运行时访问模式而导致错误共享.

- 建设性干扰大小:一个适合作为限制两个对象的组合内存占用大小和基址对齐的数字,以促进它们之间的真正共享.

在这两种情况下,这些值都是在实现质量的基础上提供的,纯粹是作为可能提高性能的提示.这些是与 alignas() 关键字一起使用的理想可移植值,目前几乎没有标准支持的可移植用途.

<小时>

这些常量与 L1 缓存行大小有什么关系?"

理论上,很直接.

假设编译器确切地知道您将在什么架构上运行 - 那么这些几乎肯定会准确地为您提供 L1 缓存行大小.(正如后面提到的,这是一个很大的假设.)

就其价值而言,我几乎总是希望这些值相同.我相信单独声明它们的唯一原因是为了完整性.(也就是说,也许编译器想要估计 L2 缓存行大小而不是 L1 缓存行大小以进行建设性干扰;不过,我不知道这是否真的有用.)

<小时>有没有一个很好的例子来展示他们的用例?"

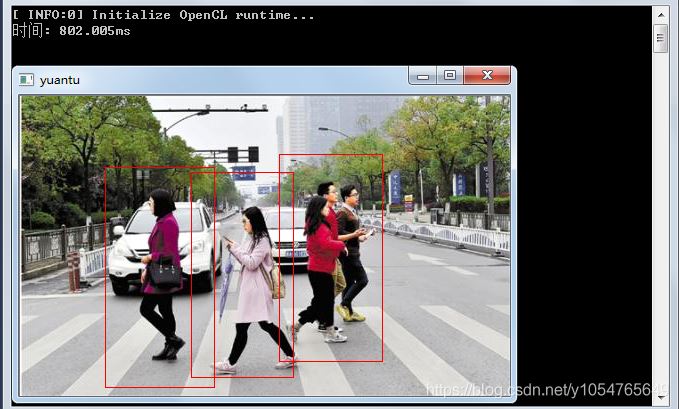

在这个答案的底部,我附上了一个很长的基准程序,它演示了错误共享和真实共享.

它通过分配一个 int 包装器数组来演示错误共享:在一种情况下,多个元素适合 L1 缓存行,而在另一种情况下,单个元素占用 L1 缓存行.在紧密循环中,从数组中选择一个固定的元素并重复更新.

它通过在包装器中分配一对整数来展示真正的共享:在一种情况下,这对整数中的两个整数不适合一起在 L1 缓存行大小中,而在另一种情况下.在一个紧密的循环中,对中的每个元素都会重复更新.

注意访问被测对象的代码不会改变;唯一的区别是对象本身的布局和对齐方式.

我没有 C++17 编译器(假设大多数人目前也没有),所以我用我自己的常量替换了有问题的常量.您需要更新这些值以使其在您的机器上准确无误.也就是说,64 字节可能是典型现代桌面硬件的正确值(在撰写本文时).

警告:测试将使用您机器上的所有内核,并分配约 256MB 的内存.不要忘记进行优化编译!

在我的机器上,输出是:

<前>硬件并发:16大小(naive_int):4alignof(naive_int): 4大小(cache_int):64alignof(cache_int): 64大小(坏对):72alignof(bad_pair): 4大小(good_pair):8alignof(good_pair): 4运行 naive_int 测试.平均时间:0.0873625 秒,无用结果:3291773运行 cache_int 测试.平均时间:0.024724 秒,无用结果:3286020运行 bad_pair 测试.平均时间:0.308667 秒,无用结果:6396272运行 good_pair 测试.平均时间:0.174936 秒,无用结果:6668457通过避免错误共享,我获得了大约 3.5 倍的加速,通过确保真实共享获得了大约 1.7 倍的加速.

<小时>两者都定义为静态 constexpr.如果您构建一个二进制文件并在具有不同缓存行大小的其他机器上执行它,这不是问题吗?当您不确定时,它如何防止这种情况下的错误共享您的代码将在哪台机器上运行?"

这确实会有问题.这些常量不能保证映射到特定目标机器上的任何缓存行大小,但旨在成为编译器可以收集的最佳近似值.

提案中对此进行了说明,并且在附录中他们给出了一些库如何在编译时根据各种环境提示和宏尝试检测缓存行大小的示例.你保证这个值至少是alignof(max_align_t),这是一个明显的下限.

换句话说,这个值应该用作你的后备案例;如果您知道,您可以自由定义一个精确的值,例如:

constexpr std::size_t cache_line_size() {#ifdef KNOWN_L1_CACHE_LINE_SIZE返回 KNOWN_L1_CACHE_LINE_SIZE;#别的返回 std::hardware_corruption_interference_size;#万一}在编译期间,如果您想假设缓存行大小,只需定义 KNOWN_L1_CACHE_LINE_SIZE.

希望这有帮助!

基准计划:

#include #include <条件变量>#include #include <功能>#include <未来>#include #include <随机>#include <线程>#include <向量>//!!!你必须更新这个才能准确!!!constexpr std::size_t 硬件破坏性干扰大小 = 64;//!!!你必须更新这个才能准确!!!constexpr std::size_t hardware_constructive_interference_size = 64;constexpr 无符号 kTimingTrialsToComputeAverage = 100;constexpr 无符号 kInnerLoopTrials = 1000000;typedef 无符号 useless_result_t;typedef double elapsed_secs_t;////////要采样的代码://包装一个 int,默认对齐方式允许错误共享结构天真_int {整数值;};静态断言(alignof(naive_int)<硬件破坏性干扰大小,");//包装一个 int,缓存对齐防止错误共享结构缓存_int {alignas(hardware_corruption_interference_size) int 值;};静态断言(alignof(cache_int)==硬件破坏性干扰大小,");//包装一对 int,故意将它们分开太远以供真正共享结构坏对{整数优先;字符填充[hardware_constructive_interference_size];整数秒;};static_assert(sizeof(bad_pair) > hardware_constructive_interference_size, "");//包装一对 int,确保它们很好地配合在一起以实现真正的共享结构good_pair {整数优先;整数秒;};static_assert(sizeof(good_pair) <= hardware_constructive_interference_size, "");//多次访问特定的数组元素模板 useless_result_t sample_array_threadfunc(锁存器闩锁,未签名的线程索引,夯;vec) {//准备计算std::random_device rd;std::mt19937 mt{ rd() };std::uniform_int_distribution距离{ 0, 4096 };自动&element = vec[vec.size()/2 + thread_index];闩锁.count_down_and_wait();//计算for (unsigned trial = 0; trial != kInnerLoopTrials; ++trial) {element.value = dist(mt);}return static_cast(element.value);}//多次访问一对元素模板 useless_result_t sample_pair_threadfunc(锁存器闩锁,未签名的线程索引,夯;一对) {//准备计算std::random_device rd;std::mt19937 mt{ rd() };std::uniform_int_distribution距离{ 0, 4096 };闩锁.count_down_and_wait();//计算for (unsigned trial = 0; trial != kInnerLoopTrials; ++trial) {pair.first = dist(mt);pair.second = dist(mt);}return static_cast(pair.first) +static_cast(pair.second);}////////实用程序://实用程序:允许线程等待所有人都准备好类线程锁{民众:显式线程锁(const std::size_t count):计数_{计数}{}void count_down_and_wait() {std::unique_lock锁{互斥体_};如果(--count_ == 0){cv_.notify_all();}别的 {cv_.wait(lock, [&] { return count_ == 0; });}}私人的:std::mutex mutex_;std::condition_variable cv_;std::size_t count_;};//实用程序:在 N 个线程中运行给定的函数std::tuple运行线程(const std::function<useless_result_t(threadlatch&, unsigned)>&功能,const unsigned num_threads) {线程闩锁{ num_threads + 1 };std::vector<std::future<useless_result_t>>期货;std::vector线程;for (unsigned thread_index = 0; thread_index != num_threads; ++thread_index) {std::packaged_task任务{std::bind(func, std::ref(latch), thread_index)};futures.push_back(task.get_future());thread.push_back(std::thread(std::move(task)));}const auto starttime = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();闩锁.count_down_and_wait();对于(自动和线程:线程){线程连接();}const auto endtime = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();const auto elapsed = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::duration<double>>(结束时间 - 开始时间).数数();useless_result_t 结果 = 0;对于(汽车和未来:期货){结果 += future.get();}返回 std::make_tuple(result, elapsed);}//实用程序:采样在 N 个线程上运行 func 所需的时间无效运行_测试(const std::function<useless_result_t(threadlatch&, unsigned)>&功能,const unsigned num_threads) {useless_result_t final_result = 0;双平均时间 = 0.0;for (unsigned trial = 0; trial != kTimingTrialsToComputeAverage; ++trial) {const auto result_and_elapsed = run_threads(func, num_threads);const auto result = std::get(result_and_elapsed);const auto elapsed = std::get(result_and_elapsed);final_result += 结果;avgtime = (avgtime * trial + elapsed)/(trial + 1);}std::cout<<平均时间:" <<平均时间<<" 秒,无用的结果:" <<最后结果<<std::endl;}int main() {const auto cores = std::thread::hardware_concurrency();std::cout <<"硬件并发:" <<核心<vec;vec.resize((1u << 28)/sizeof(naive_int));//分配 256 mibibytesrun_tests([&](threadlatch&latch, unsigned thread_index) {返回 sample_array_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, vec);},核心);}{std::cout <<正在运行 cache_int 测试."<<std::endl;std::vectorvec;vec.resize((1u << 28)/sizeof(cache_int));//分配 256 mibibytesrun_tests([&](threadlatch&latch, unsigned thread_index) {返回 sample_array_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, vec);},核心);}{std::cout <<运行 bad_pair 测试."<<std::endl;bad_pair p;run_tests([&](threadlatch&latch, unsigned thread_index) {返回 sample_pair_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, p);},核心);}{std::cout <<运行 good_pair 测试."<<std::endl;good_pair p;run_tests([&](threadlatch&latch, unsigned thread_index) {返回 sample_pair_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, p);},核心);}} C++17 added std::hardware_destructive_interference_size and std::hardware_constructive_interference_size. First, I thought it is just a portable way to get the size of a L1 cache line but that is an oversimplification.

Questions:

- How are these constants related to the L1 cache line size?

- Is there a good example that demonstrates their use cases?

- Both are defined

static constexpr. Is that not a problem if you build a binary and execute it on other machines with different cache line sizes? How can it protect against false sharing in that scenario when you are not certain on which machine your code will be running?

The intent of these constants is indeed to get the cache-line size. The best place to read about the rationale for them is in the proposal itself:

http://www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg21/docs/papers/2016/p0154r1.html

I'll quote a snippet of the rationale here for ease-of-reading:

[...] the granularity of memory that does not interfere (to the first-order) [is] commonly referred to as the cache-line size.

Uses of cache-line size fall into two broad categories:

- Avoiding destructive interference (false-sharing) between objects with temporally disjoint runtime access patterns from different threads.

- Promoting constructive interference (true-sharing) between objects which have temporally local runtime access patterns.

The most sigificant issue with this useful implementation quantity is the questionable portability of the methods used in current practice to determine its value, despite their pervasiveness and popularity as a group. [...]

We aim to contribute a modest invention for this cause, abstractions for this quantity that can be conservatively defined for given purposes by implementations:

- Destructive interference size: a number that’s suitable as an offset between two objects to likely avoid false-sharing due to different runtime access patterns from different threads.

- Constructive interference size: a number that’s suitable as a limit on two objects’ combined memory footprint size and base alignment to likely promote true-sharing between them.

In both cases these values are provided on a quality of implementation basis, purely as hints that are likely to improve performance. These are ideal portable values to use with the

alignas()keyword, for which there currently exists nearly no standard-supported portable uses.

"How are these constants related to the L1 cache line size?"

In theory, pretty directly.

Assume the compiler knows exactly what architecture you'll be running on - then these would almost certainly give you the L1 cache-line size precisely. (As noted later, this is a big assumption.)

For what it's worth, I would almost always expect these values to be the same. I believe the only reason they are declared separately is for completeness. (That said, maybe a compiler wants to estimate L2 cache-line size instead of L1 cache-line size for constructive interference; I don't know if this would actually be useful, though.)

"Is there a good example that demonstrates their use cases?"

At the bottom of this answer I've attached a long benchmark program that demonstrates false-sharing and true-sharing.

It demonstrates false-sharing by allocating an array of int wrappers: in one case multiple elements fit in the L1 cache-line, and in the other a single element takes up the L1 cache-line. In a tight loop a single, a fixed element is chosen from the array and updated repeatedly.

It demonstrates true-sharing by allocating a single pair of ints in a wrapper: in one case, the two ints within the pair do not fit in L1 cache-line size together, and in the other they do. In a tight loop, each element of the pair is updated repeatedly.

Note that the code for accessing the object under test does not change; the only difference is the layout and alignment of the objects themselves.

I don't have a C++17 compiler (and assume most people currently don't either), so I've replaced the constants in question with my own. You need to update these values to be accurate on your machine. That said, 64 bytes is probably the correct value on typical modern desktop hardware (at the time of writing).

Warning: the test will use all cores on your machines, and allocate ~256MB of memory. Don't forget to compile with optimizations!

On my machine, the output is:

Hardware concurrency: 16 sizeof(naive_int): 4 alignof(naive_int): 4 sizeof(cache_int): 64 alignof(cache_int): 64 sizeof(bad_pair): 72 alignof(bad_pair): 4 sizeof(good_pair): 8 alignof(good_pair): 4 Running naive_int test. Average time: 0.0873625 seconds, useless result: 3291773 Running cache_int test. Average time: 0.024724 seconds, useless result: 3286020 Running bad_pair test. Average time: 0.308667 seconds, useless result: 6396272 Running good_pair test. Average time: 0.174936 seconds, useless result: 6668457

I get ~3.5x speedup by avoiding false-sharing, and ~1.7x speedup by ensuring true-sharing.

"Both are defined static constexpr. Is that not a problem if you build a binary and execute it on other machines with different cache line sizes? How can it protect against false sharing in that scenario when you are not certain on which machine your code will be running?"

This will indeed be a problem. These constants are not guaranteed to map to any cache-line size on the target machine in particular, but are intended to be the best approximation the compiler can muster up.

This is noted in the proposal, and in the appendix they give an example of how some libraries try to detect cache-line size at compile time based on various environmental hints and macros. You are guaranteed that this value is at least alignof(max_align_t), which is an obvious lower bound.

In other words, this value should be used as your fallback case; you are free to define a precise value if you know it, e.g.:

constexpr std::size_t cache_line_size() {

#ifdef KNOWN_L1_CACHE_LINE_SIZE

return KNOWN_L1_CACHE_LINE_SIZE;

#else

return std::hardware_destructive_interference_size;

#endif

}

During compilation, if you want to assume a cache-line size just define KNOWN_L1_CACHE_LINE_SIZE.

Hope this helps!

Benchmark program:

#include <chrono>

#include <condition_variable>

#include <cstddef>

#include <functional>

#include <future>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

#include <thread>

#include <vector>

// !!! YOU MUST UPDATE THIS TO BE ACCURATE !!!

constexpr std::size_t hardware_destructive_interference_size = 64;

// !!! YOU MUST UPDATE THIS TO BE ACCURATE !!!

constexpr std::size_t hardware_constructive_interference_size = 64;

constexpr unsigned kTimingTrialsToComputeAverage = 100;

constexpr unsigned kInnerLoopTrials = 1000000;

typedef unsigned useless_result_t;

typedef double elapsed_secs_t;

//////// CODE TO BE SAMPLED:

// wraps an int, default alignment allows false-sharing

struct naive_int {

int value;

};

static_assert(alignof(naive_int) < hardware_destructive_interference_size, "");

// wraps an int, cache alignment prevents false-sharing

struct cache_int {

alignas(hardware_destructive_interference_size) int value;

};

static_assert(alignof(cache_int) == hardware_destructive_interference_size, "");

// wraps a pair of int, purposefully pushes them too far apart for true-sharing

struct bad_pair {

int first;

char padding[hardware_constructive_interference_size];

int second;

};

static_assert(sizeof(bad_pair) > hardware_constructive_interference_size, "");

// wraps a pair of int, ensures they fit nicely together for true-sharing

struct good_pair {

int first;

int second;

};

static_assert(sizeof(good_pair) <= hardware_constructive_interference_size, "");

// accesses a specific array element many times

template <typename T, typename Latch>

useless_result_t sample_array_threadfunc(

Latch& latch,

unsigned thread_index,

T& vec) {

// prepare for computation

std::random_device rd;

std::mt19937 mt{ rd() };

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> dist{ 0, 4096 };

auto& element = vec[vec.size() / 2 + thread_index];

latch.count_down_and_wait();

// compute

for (unsigned trial = 0; trial != kInnerLoopTrials; ++trial) {

element.value = dist(mt);

}

return static_cast<useless_result_t>(element.value);

}

// accesses a pair's elements many times

template <typename T, typename Latch>

useless_result_t sample_pair_threadfunc(

Latch& latch,

unsigned thread_index,

T& pair) {

// prepare for computation

std::random_device rd;

std::mt19937 mt{ rd() };

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> dist{ 0, 4096 };

latch.count_down_and_wait();

// compute

for (unsigned trial = 0; trial != kInnerLoopTrials; ++trial) {

pair.first = dist(mt);

pair.second = dist(mt);

}

return static_cast<useless_result_t>(pair.first) +

static_cast<useless_result_t>(pair.second);

}

//////// UTILITIES:

// utility: allow threads to wait until everyone is ready

class threadlatch {

public:

explicit threadlatch(const std::size_t count) :

count_{ count }

{}

void count_down_and_wait() {

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock{ mutex_ };

if (--count_ == 0) {

cv_.notify_all();

}

else {

cv_.wait(lock, [&] { return count_ == 0; });

}

}

private:

std::mutex mutex_;

std::condition_variable cv_;

std::size_t count_;

};

// utility: runs a given function in N threads

std::tuple<useless_result_t, elapsed_secs_t> run_threads(

const std::function<useless_result_t(threadlatch&, unsigned)>& func,

const unsigned num_threads) {

threadlatch latch{ num_threads + 1 };

std::vector<std::future<useless_result_t>> futures;

std::vector<std::thread> threads;

for (unsigned thread_index = 0; thread_index != num_threads; ++thread_index) {

std::packaged_task<useless_result_t()> task{

std::bind(func, std::ref(latch), thread_index)

};

futures.push_back(task.get_future());

threads.push_back(std::thread(std::move(task)));

}

const auto starttime = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

latch.count_down_and_wait();

for (auto& thread : threads) {

thread.join();

}

const auto endtime = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

const auto elapsed = std::chrono::duration_cast<

std::chrono::duration<double>>(

endtime - starttime

).count();

useless_result_t result = 0;

for (auto& future : futures) {

result += future.get();

}

return std::make_tuple(result, elapsed);

}

// utility: sample the time it takes to run func on N threads

void run_tests(

const std::function<useless_result_t(threadlatch&, unsigned)>& func,

const unsigned num_threads) {

useless_result_t final_result = 0;

double avgtime = 0.0;

for (unsigned trial = 0; trial != kTimingTrialsToComputeAverage; ++trial) {

const auto result_and_elapsed = run_threads(func, num_threads);

const auto result = std::get<useless_result_t>(result_and_elapsed);

const auto elapsed = std::get<elapsed_secs_t>(result_and_elapsed);

final_result += result;

avgtime = (avgtime * trial + elapsed) / (trial + 1);

}

std::cout

<< "Average time: " << avgtime

<< " seconds, useless result: " << final_result

<< std::endl;

}

int main() {

const auto cores = std::thread::hardware_concurrency();

std::cout << "Hardware concurrency: " << cores << std::endl;

std::cout << "sizeof(naive_int): " << sizeof(naive_int) << std::endl;

std::cout << "alignof(naive_int): " << alignof(naive_int) << std::endl;

std::cout << "sizeof(cache_int): " << sizeof(cache_int) << std::endl;

std::cout << "alignof(cache_int): " << alignof(cache_int) << std::endl;

std::cout << "sizeof(bad_pair): " << sizeof(bad_pair) << std::endl;

std::cout << "alignof(bad_pair): " << alignof(bad_pair) << std::endl;

std::cout << "sizeof(good_pair): " << sizeof(good_pair) << std::endl;

std::cout << "alignof(good_pair): " << alignof(good_pair) << std::endl;

{

std::cout << "Running naive_int test." << std::endl;

std::vector<naive_int> vec;

vec.resize((1u << 28) / sizeof(naive_int)); // allocate 256 mibibytes

run_tests([&](threadlatch& latch, unsigned thread_index) {

return sample_array_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, vec);

}, cores);

}

{

std::cout << "Running cache_int test." << std::endl;

std::vector<cache_int> vec;

vec.resize((1u << 28) / sizeof(cache_int)); // allocate 256 mibibytes

run_tests([&](threadlatch& latch, unsigned thread_index) {

return sample_array_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, vec);

}, cores);

}

{

std::cout << "Running bad_pair test." << std::endl;

bad_pair p;

run_tests([&](threadlatch& latch, unsigned thread_index) {

return sample_pair_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, p);

}, cores);

}

{

std::cout << "Running good_pair test." << std::endl;

good_pair p;

run_tests([&](threadlatch& latch, unsigned thread_index) {

return sample_pair_threadfunc(latch, thread_index, p);

}, cores);

}

}

这篇关于理解 std::hardware_corruption_interference_size 和 std::hardware_constructive_interference_size的文章就介绍到这了,希望我们推荐的答案对大家有所帮助,也希望大家多多支持编程学习网!

本文标题为:理解 std::hardware_corruption_interference_size 和 std::ha

- 使用 __stdcall & 调用 DLLVS2013 中的 GetProcAddress() 2021-01-01

- 将函数的返回值分配给引用 C++? 2022-01-01

- 如何提取 __VA_ARGS__? 2022-01-01

- 从父 CMakeLists.txt 覆盖 CMake 中的默认选项(...)值 2021-01-01

- XML Schema 到 C++ 类 2022-01-01

- DoEvents 等效于 C++? 2021-01-01

- 哪个更快:if (bool) 或 if(int)? 2022-01-01

- GDB 不显示函数名 2022-01-01

- OpenGL 对象的 RAII 包装器 2021-01-01

- 将 hdc 内容复制到位图 2022-09-04